"Reviewing some thirty years of research on the estate of Magnus Hirschfeld and of the Institute for Sexual Science, there is a very simple result: one thing leads to another."

In this paper Ralf Dose describes the thirty year long research on the work of Magnus Hirschfeld, the German sexologist and founder of the Institute for Sexual Science. Ralf Dose offers insights into how the Magnus Hirschfeld society retrieved some of the "Treasure Troves" of Hirschfeld's personal belongings and items from his institute, like his death mask, his exile guest book and a collection of Japanese dildos.

What do you think are the most valuable lessons to be learned from the 30 years experience of the Magnus Hirschfeld society? And whose "Treasure Troves" would you try to retrieve? The full paper can be read below. Feel free to read, comment, discuss and let us know you own experiences.

To read Ralf Dose's full paper click on "Read more"

Thirty

Years of Collecting Our History – Or: How to Find Treasure Troves

Ralf Dose,

Magnus Hirschfeld Society, Berlin

When

founded in 1982/83, the Magnus Hirschfeld Society’s aim was to preserve the

heritage of the sexual scientist Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935) for posterity,

and to do research on his work. At that time, this was connected with the aim of

the GL(BT) movement, which was to

claim a history of its own. When looking more closely into the matter of the work

and achievements of Dr. Hirschfeld, we soon noticed that the focus on GL(BT)

history was far too narrow to capture the importance of Hirschfeld both for

sexual science and for cultural history.[1]

My paper explores

some of the steps we took in finding the material remnants of Hirschfeld’s cultural

heritage over some thirty years of research and collecting. It should be read

together with the corresponding paper by Don McLeod on “Serendipity and the

Papers of Magnus Hirschfeld: The Case of Ernst Maass,” where he gives a lot of

detail about one of our joint searches. And, please, keep in mind that my

English is not as good as my German. Thus, the German version of this paper

sometimes is more specific than this one.[2]

Preface

When we

started to look for Hirschfeld’s heritage, it was a common belief that hardly

anything of Hirschfeld’s personal belongings or items from his Institute for

Sexual Science would have survived. Manfred Herzer compiled a preliminary short

list of single Hirschfeld letters which survived in various archives, libraries,

and private collections. It was known, too, that some single books from the

library of the Institute had survived in private or public libraries. But no

whole collection was known or could be expected to exist in a library or an

archive. This was due to the political and personal situation at the time of

Hirschfeld’s death. The Institute’s furniture and assets, as well as all the

equipment of Hirschfeld’s private rooms and his personal papers, were thought

to be lost forever.

Members of

our society had been in contact with a few contemporaries who had been active

members of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (SHC), had worked for awhile

in some position at the Institute, or had taken part in the work of the World

League for Sexual Reform, for example, Kurt Hiller[3],

Erhart Löhnberg[4], Günter

Maeder[5],

Bruno Vogel[6],

and Herbert Lewandowski[7].

Others had been clients of the Institute. We got their stories.[8]

But how should we proceed from there?

The first

step in a probate case is always to search for the legal heirs or heirs who are

mentioned in a will. In the case of Dr. Hirschfeld that meant: What happened to

his Foundation (the Institute), and where did his personal belongings and

assets go? Since Hirschfeld had died in exile, at least those items in his

possession could have been given to his heirs. All the assets of the

Foundation, of course, did not belong to Hirschfeld any more, and, even worse,

were located in (Nazi) Germany. He was not in a position to leave those assets

to his heirs.[9] Thus, there

might be archives which could have more information, or even possess items.

One of the

first sources was found by Manfred Baumgardt: German restitution and

compensation files.[10] But they

contained little information about the Institute’s archive and library, and for

other items, such as paintings or other works of art that had been in the

Institute, they offered nearly nothing—so that already the restitution

authorities had dropped that part of the case. Concerning the Foundation, it

became clear that German courts in the 1950s ruled that it was dissolved

legally, so that there was no chance of a simple re-establishment.

These files

contained a copy of Hirschfeld’s last will and testament, filed in Nice, too.[11]

There were two heirs named—Karl Giese, and Li Shiu Tong—and several persons

listed who should get a legacy, which consisted of an amount of money. Those

legacies were given to members of the larger family, to friends, and to

long-time servants for their services. In addition, there was the name of a storage

company in Paris, where Hirschfeld had stored away items. This was much more

than outsiders could expect, because in Germany wills are not public records

and access is restricted to legally entitled persons. So we were lucky to find

a photocopy of that will as part of the restitution files, which were in an

archive with less strict access rules.

Soon we

realized that we knew hardly anything about the Institute for Sexual

Science—about the persons working there, or about the institutions they had created

for their work, or about the scientific or social context in which they worked.

Every name, every organization, and every political connection mentioned had to

be looked up somewhere—if there was some reference material at all. There existed

no manual for the history of sexual science.[12]

There were no biographical dictionaries referring to those persons of interest

to us.[13]

Only the older generation had made it into the “Pagel”,[14]

but the careers of most members of the younger generation of researchers or

physicians ended before they could leave their mark in a dictionary. And where

should we look up all those persons who weren’t physicians or writers, but

jurists[15],

politicians of the second or third tier, or just activists in lay movements, or

even domestic personnel? And there was no way of systematically searching for

people who had come as visitors, guests, or patients into the house, or had

some relation with its collaborators.

Our

research method was not a systematic one. Instead, we tried to grab every clue

and loose end we could find. Only from today’s point of view can we describe

more systematically what we did.

Some questions to

start with:

a) What are we looking for?

Objects:

Books, pictures, photographs, letters, manuscripts, documents

Personal

memories (diaries)

Official

memories: Files, (public) records

b) Whom do

we look for?

Legal

heirs

Family

members

Friends

Correspondence

partners

Collaborators

c) Where do

we search?

Libraries

and Archives–Topic catalogues, Finding aids

Private

Collections

(Auto-)Biographies

(Dissertations!)

City

directories, telephone directories

Newspaper

articles

Recently:

genealogical databases and Internet searches in general

I’ll

restrict myself to some details and stories referring to questions b) and c):

Whom, and where do we search?—The answer to the first question would have been

“Everything!” in the beginning of our work. It was only through accumulated

findings and knowledge that we were able to be more specific about what to

expect in a special place.

The Heirs

According

to Hirschfeld’s last will and testament, there were two heirs—Karl Giese and Li

Shiu Tong—but searching for them turned out to be difficult from the beginning:

Karl Giese had committed suicide in Brno in 1938, and the lawyer Karl Fein, who

would have been able to inform us about Karl’s estate, did not survive the German

occupation of Czechoslovakia. For us, research in Czechoslovakia was complicated

due to the language barrier. Details about Giese’s life after Hirschfeld’s

death were found later in a correspondence with the domestic worker Adelheid

Rennhack (see below), in a correspondence with the Institute’s physician Max

Hodann, as well as—much later—in a correspondence with Ernst Maass (see below).

But from those letters we could only learn that Giese did not get his share of

the Hirschfeld assets (or only got it very late). At least, he did not have

access to the Hirschfeld diaries in 1936. We expect to learn more from the

research that Hans Soetaert recently conducted in the Czech Republic.

As for Li

Shiu Tong, we knew that he had lived in Zurich but had avoided any contact with

Germans and especially German authorities. In the beginning of 1960 he had

relocated to Hong Kong. To search for a Chinese with the name of “Li” in Hong

Kong seemed impossible to us, especially as we did not know the Chinese

characters of his name. But even after we had his name in his own handwriting, the

search turned out to be fruitless.[18]

Unexpected good luck (and the Internet) helped with this:[19]

From time to time, I do a routine search for “Magnus Hirschfeld”. One slightly

drunken night, this routine search went astray into a newsgroup search (where I

normally did not search): Entries came up upside down, the oldest on top,

entered shortly after the creation of the WWWorld (17 March 1994).

|

As you may

easily see, it took some efforts to find the author: Somehow, I managed to find

out that the author was a certain “Adam Smith”, but you cannot reasonably search

for “Adam Smith” on the Internet, and ten-year-old e-mail-addresses are

useless. I spent a sleepless night on many trials to find a clue, and finally

found a website where the words “steakface” and “datapanik” showed up. I sent

an e-mail to the owner, and after ten minutes, I had a response from Toronto.

Yes, that request was posted by me, and everything is still sitting in my

cellar. You can imagine that I was close to a heart attack. Funny enough, the real

name of the person was “Adam Smith”. The next day, he sent me some photographs of

a suitcase and its contents, which gave me another heart attack: There was,

among lots of other things, the Hirschfeld death mask, a booklet named

“Testament. Heft II”, there were photographs, and copies of rare journals.

|

| Hirschfeld's Testament. © Adam Smith |

|

| The Death Mask © Adam Smith |

Adam told

me that he had known Mr. Li only from meetings in the elevator of the building,

exchanging a friendly “Good morning, Mr. Li”. He had come across these items

because as a student, he earned some money by cleaning out the dumpster of the

building once a week. And one day, after Mr. Li’s death, he found all those

strange things in that room, which he thought should not be just thrown away.

He could not read German, and, of course, not at all old German handwriting—but

nevertheless, after asking a family member for permission, he put those items

into a suitcase and took everything home. His later wife, Nancy, at that time a

medical student, had heard the name of Hirschfeld, so they knew that they had

found something important. Adam, belonging to a younger generation, was ahead

of time when he posted his findings on the Internet: in 1994 researchers in the

field of history would not really use this medium. Thus, he got some strange answers,

but nothing that convinced him of donating those items to anyone.

The suitcase. © Adam Smith

Now, with

the address of Li’s last residence, I wanted to find his family. And knowing the

year of his death, I started to look for his will or a probate file. I am now a

professional probate researcher, but at that time, I did not know anything and

had to learn how to do such a search. I knew from Adam that Li owned his

apartment. In Germany, with an address, you can easily find information about a

real estate. But in Canada, I had to learn, you need to know the name of the

present owner, and in addition, you should know whether the building is on

federal, provincial, or communal ground. As additional information, Adam had

heard family rumours that Mr. Li had given parts of his collection to local

archives. Thus, I started an Internet search for “Li collection” in British

Columbia archives and libraries—to no avail. Since I did not know the name of

the present owner of Mr. Li’s apartment, I asked a friend who was going on a

holiday to Vancouver to check the building’s inhabitants. Being German, I had

expected the names of the inhabitants to be listed at the entrance intercom,

not just apartment numbers. But Adam had provided us with the apartment number

so my friend could ask the building manager for the name of the inhabitant, and

got it—but that did not help, since she had rented the apartment.

Later, I

myself had some correspondence with the building manager, and she directed me

to a former neighbour of Mr. Li, with an incomplete address somewhere in Canada—a

name, a city, and a postcode; no street address. Nevertheless, my letter

reached her, and she was very polite and gave me more information about Mr. Li,

who had loved to travel, and with his wife had often visited his son in New

York City. It was only after some more research that I found out: Mr. Li was

never married, and there was no son in New York City. (I had identified a

possible person from some Internet searches, but did never get an answer from

that one.)

At the same

time, through Internet research, I had learned that it was possible to get

access to Canadian probate files, but a death date would be needed. I did not

have an exact death date, just a year and a probable month. Canadian probate

court websites suggested engaging local researchers, but their cost per hour was

far beyond my means. So I sent a request to the probate court I had identified

as the one that might have the file of Mr. Li myself, offering reimbursement

for any copies. For about half a year, there was nothing; and I even forgot

that search. Then, one day, I had a big envelope from Canada in my mailbox. It

contained a complete copy of the probate file of Mr. Li, without any charge.

Maybe, there was some queer person on duty at the Probate Court? The file

contained the addresses of all those family members who had become heirs of Mr.

Li. Again, addresses of 1994 were outdated in 2003, but it was easy enough to

find an actual address of the executor—one of the younger brothers of Mr. Li,

who had some 24 siblings.

I sent a

letter, and received a fax confirming that the family had more items from their

brother’s and uncle’s estate, especially books, and asked for a “reasonable

offer” as they wanted to sell everything. I told Adam about this, and in his

answer he came up with the suggestion that he and Nancy wanted to donate their

suitcase to the Magnus Hirschfeld Society: “Should I send it or will someone

come and collect it in Toronto?” At this point, I decided to go to Canada,

though I did not have the money for such an excursion, nor did the Hirschfeld

Society. I told Dr. Hermann Simon of the Centrum Judaicum in Berlin about this

new development, and he kindly suggested that I should book a flight

immediately and send him the bill. And so, with additional help from Canadian

and U.S. friends who offered to invite me for lectures, I was able to go to

Toronto and Vancouver in February, 2003. First, I visited Adam Smith and

collected the donated suitcase, and then I spent a few days in Vancouver. Li

Shiu Tong’s brother invited me to his office, showed me Chinatown, and later

even invited me to his home to have a closer look at the books they were

keeping. I made a list and later from home we offered a price we found

reasonable. Unfortunately, the family expected much more—far beyond our means.

So we had to wait. Later we were able to come to an agreement that was acceptable

for both sides. And so all the books from the Hirschfeld estate that had been

in Li Shiu Tong’s possession when he died came back to Berlin in 2006.[20]

I wanted to

find out more about Li’s last years, but the family could (or would) not tell

much. Mr. Li, the much younger brother, put it like this: “My brother was a

strange man—he did not drink, he did not smoke, and he did not like women.” My

answer to this was: “I’m a bit strange, too—but I drink.” Li Shiu Tong had

lived alone in his apartment on Barclay Street, halfway between downtown and

boystown, and he was as sportsman, playing tennis. I could not find out who was

his tennis partner. But, I found his tomb, after calling all and every cemetery

in Vancouver, and on my last day in Canada, I was able to put some flowers

there in order to honour a true friend of Magnus Hirschfeld.[21]

When

talking about the search for the Hirschfeld heirs, I should mention, too, one

of our big mistakes. Actually, we only found out this year that we made a

mistake:

We had the

information who was Hirschfeld’s executor, together with an address in Paris,

France. The source included the information that Dr. Franz Herzfelder had

closed his law office at the end of the 1960s, and therefore asked the Berlin

probate court to name someone else as an executor (which was never done). Since

we had no further information, we imagined this Dr. Herzfelder as of the same

age as Hirschfeld, and supposed he was no longer alive when we started our work

in the 1980s. At that time—without the Internet—researching a person abroad was

much more difficult, and we did not really know how to proceed. Thus, we never

consulted a Paris phone book (I am not even sure that such a phone book would

have been available easily in Berlin). Only after the millennium were there a

few entries on the Internet about Dr. Herzfelder, but still without any dates.

The dates were only published in 2007[22]—and

we consulted this book thoroughly only this year, when we were searching for

someone else. There he was: Dr. Herzfelder died in Paris in 1998. We could have

asked him, if only we had known.

Family Members

The next

step when searching for an estate would be looking for offspring, and if there

is no offspring of the testator one would look for the children of his

siblings. In Hirschfeld’s case it was clear that it was the wider family which

we had to look for. Which meant, in the first instance, we had to find out who

(and where) they were.

A few

connections (parents, siblings) are mentioned in Hirschfeld’s writings, but

even there details are missing, and in most cases there are no exact data.

Especially on his mother’s side there was nothing (even now, the date of his

mother’s death is unknown). From the files of the compensation court we knew a

few names of persons who had survived the Shoah, but, again, the addresses given

were so incomplete that a search seemed useless: Where do you look for “Franz

Mann, Africa”?

One of

those strange searches for family members may be mentioned. In his part of the

little booklet given to his sister Franziska for her sixtieth birthday,

Hirschfeld mentions that their father had a beloved brother named Eduard. This

brother had travelled to California around 1848, “to bring bodily nourisment, and

above all nourishment for their souls” to the settlers and gold-seekers. On his

way back to Europe in the 1850s he had drowned off the coast of South Carolina.

As a memory to his brother, Hermann Hirschfeld had named his second son Eduard,

and the name of Franziska, of course, had a connection to San Francisco, the

last residence of this brother.[23]

The question was: Could we substantiate such a family legend with facts? City

directories of San Francisco for those years don’t exist, and the newspaper

lists of arriving passengers only list First Class passengers and neglect the

Steerage passengers. But, there was the sinking of the ship. In fact, there was

a ship that sank in a storm in 1857 near the coast of South Carolina which was

bringing passengers from the west coast to New York. The spectacular story of

the rescue of the treasures of the SS Central America has been published,[24]

and the passenger list has been reconstructed.[25]

Eduard Hirschfeld must have made some fortune in California—he could afford First

Class for his way back.

Completely

out of the blue, many years ago a granddaughter of Hirschfeld’s sister Jenny

left a message on our answering machine. She is living today in Melbourne,

Australia, with her family, and one night had watched Rosa von Praunheim’s film

“The Einstein of Sex” on local TV. She wanted to tell us that she was a grand

niece of this great man. According to our research we knew that her father,

Jenny’s son Günter Rudi Hauck, had escaped the Nazis to Australia, but we had

no additional information about his family. When I called her back and said,

“You must be a daughter of Günter Rudi Hauck,” she exclaimed in surprise, “How

do you know?” Gaby and Leon Cohen visited us twice in Berlin, and gave us

copies of family photographs and papers, and they have become good friends.

Gaby

Cohen at the tomb of her great aunt Franziska Mann,

Berlin-Weissensee,

September 2009. © Ralf Dose

Even “Franz

Mann, Africa” could be found recently. A member of his family had the (wrong)

idea that there might be a connection with the family of the writer Thomas Mann

(because of the married name of Hirschfeld’s sister Franziska). We had to

disappoint her, but could replace the expected famous relative with another

one, and in exchange got a lot of information about the complicated family life

of Franz Mann.

During the

last twenty years, the possibilities of family research have improved very

much, and more improvements are to be expected through ongoing digitalization

of more sources. Using a lot of various genealogical databases and combining

the results with data from already digitalized registers, it is now possible to

get plausible results even from a beginning with very fragmentary data.

A good

example for such a search and its result is the search for Ernst Maass, a

second grade cousin (and great nephew). Don McLeod helped us out when we had

made a bad research mistake, and subsequently he found another treasure trove.

He tells this story in his paper “Serendipity and the Papers of Magnus Hirschfeld:

The Case of Ernst Maass”.

We are

grateful for the result of this search, since we were given a large amount of

correspondence, photographs, documents, and genealogical notes by Ernst Maass.[26]

Those genealogical notes made it possible for the first time to add the side of

Hirschfeld’s mother to the family tree,[27]

which leads to a fascinating insight: many more members of the larger family

had been involved in the work of the Institute for Sexual Science than we had

expected. They worked there as students or as physicians, or they helped

securing finances.

Background Searches

Background searches

and social settings quickly combine the search for persons with the history of

institutions. The name of Hirschfeld leads to the Scientific-Humanitarian

Committee, the Society for Sexual Science (and Eugenics, and Sexual Politics)

(Gesellschaft für Sexualwissenschaft (und Eugenik/Eugenetik, und Sexualpolitik)),

the Institute for Sexual Science,[28]

and the World League for Sexual Reform[29].

Attention, too, has to be given to publications like Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (Yearbook for Sexual Intermediates), Zeitschrift für Sexualwissenschaft (Journal of Sexual

Science), Mitteilungen des WhK (Newsletter of the SHC)[30],

Die Aufklärung (Enlightenment)[31].

The co-authors of Hirschfeld’s books, and the journals edited by collaborators

(e.g., Die Ehe/Marriage), should not

be neglected —all of them add a crowd of involved people.

Thus, it is

not really surprising that after some ten years there was a moment in our research

when we got the impression that though we had a growing mass of material we

were losing the overview. This happened when—due to political developments in

Germany after 1989—we were able to employ a larger number of researchers for a

limited time with labour office money. With the help of these colleagues we

created a chronological table of events at the Institute, where we tried to

compile all the details we knew already, including the sources. We never

published this chronic, since its fragmentary character was completely clear to

us. Anyway, this was a good working instrument for our upcoming research: To

keep track of what we already knew, and how we knew it.

This is the

place to remember a defunct institution and its former director, to whom we owe

much for this period of our research: the Library for Medical and Science

History at the Humboldt University and Dr. Kasbohm—she always knew in advance

what we needed. The library has become part of the Humboldt University Library.

Before the computer age, this library had one big advantage: There was not only

a highly sophisticated topical catalogue, but an extensive personal name

catalogue, too. It contained the sources for even minimal notices like “Professor

X was called on the chair for Y in Z”. Jubilee notes and rare essay collections

were easy to find there—and regularly you could fetch the original from the

shelves immediately.

Two early

examples for searches before the Internet age may be presented here:

a) in a

letter by Hirschfeld written in exile in Paris he mentions: “Zammert has gone

to Wiesbaden.” The physician Edmond Zammert—this was known—had made it possible

for Hirschfeld to open his Institute again in Paris. So we pondered why someone

who was safe from the Nazis would go back to Nazi Germany? He must have had

strong reasons—maybe family? Looking into the phone book of Wiesbaden in the

1980s showed nearly a dozen namesakes. We wrote letters to all of them, and got

several answers: They did not know Edmond Zammert. But then the last answer

came from an elderly lady who presented herself as Edmond Zammert’s daughter.

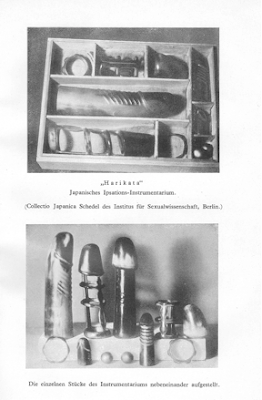

She invited me to her house—one of the best neighbourhoods in Wiesbaden on top

of the Neroberg, and after a talk over the coffee table on a beautiful balcony,

she finally placed a little wooden box with Japanese dildos between the cups

and plates, saying “I do like those, but you cannot have them on the

piano—people would talk!”

In this case, it was even very easy to find out

that the little box had been in the Institute’s collection: there is a

photograph in one of Hirschfeld’s books.[32]

Today, the box is on loan from the Magnus Hirschfeld Society to the Jewish

Museum in Berlin. Ms. Zammert had got more items from her father, but when she

was in need of some money she sold them to a Wiesbaden antique shop run by Otto

Valentiner, a friend and a tenant in her house. Otto Valentiner sold his firm

around 1992, and is said to have lived in South America later. We never got an

answer to our request to whom he had sold those items. Ms. Zammert, who needed

nursing during her last years, left her house to a family that cared for her.

We asked for permission to search the attic for more treasures, but did not get

any answer.

b) With the

World League for Sexual Reform, Hirschfeld had organized a series of international

conferences (Copenhagen 1928, London 1929, Vienna 1930, and Brno 1932). There

were always local organizers. The congress volume for 1930 was edited by Norman

Haire, but most of his correspondence from those days did not survive. Ilse

Kokula alerted us about Dora Russell’s autobiography,[33]

which includes a section about the London congress.[34]

It was very clear from that book that Dora Russell had done most of the

organizational work for the congress. Organizing a conference at that time

meant writing letters. The resulting question was: where are the papers of Dora

Russell? The few obituaries we found did not say anything about that. We sent a

request to Sheila Rowbotham, and got in return “Oh—that is an interesting

question.” It seemed that nobody had cared so far for those papers at all. My

last idea was to send a recommended letter “To the Executor of the late Mrs.

Dora Russell” in Porthcurno—a small Cornwall village where she had lived. The

idea behind this was simple: In such a small village the postmaster will know

(or can easily find out) who cares for the estate of such a prominent former

inhabitant. Against all hope this trick worked: It was only ten days later that

I had a letter from Dora Russell’s daughter Kate. She had come to her mother’s

house from Canada in order to care for the last steps of the estate’s

distribution. She told us that they were waiting for the government’s

permission to export the papers to Amsterdam’s IISG/IISH. If we needed access

to the papers immediately, she offered to do that the same winter in

Porthcurno—but we should keep in mind that everything was packed, and there was

no heating in the house. The keys would be with the village mayor. Due to

financial reasons, I was not able to accept this kind offer right on the spot.

We waited until

the papers had reached Amsterdam, and with the kind help of Heiner Becker I was

the first one to have a closer look at those fifty mover’s boxes of correspondence,

which were not catalogued at that time. Thus, I found lots of details about the

WLSR which cannot be drawn from the printed congress reports.[35]

In addition, there was some correspondence with German emigrants after 1933.

The Institute’s physician Max Hodann, whose daughter Renate attended Dora Russell’s

Beacon Hill School for awhile, had lived there in 1936 himself when he was

struggling for some kind of new existence in Britain. His letters to her lead

to many other archives, where there were more details about this emigrant’s

fate.[36]

Lots of papers in the Dora Russell collection (which has been catalogued since)

still wait for readers.[37]

I may add

an example from recent times. Over many years, the writer Kurt Hiller was one

of the most important collaborators of Hirschfeld in the Scientific-Humanitarian

Committee. Access to his papers was one of the idle desires of literature

historians of all kinds, as well as ours. Hiller’s last companion, Horst H.W.

Müller, denied access for everyone, and did not even answer letters. The Kurt

Hiller Society eventually got hold of those papers[38]

after Horst H.W. Müller had committed suicide—no one had known about it, so the

circumstances of saving Hiller’s papers make an adventurous story of sorts.

Since we are on very friendly terms with the Kurt Hiller Society, we were able

to make use of many parts of that correspondence. One of the projects that

profited much was the biography of Bruno Vogel[39],

a young writer who had been working at the Institute for awhile. But the most

intriguing find was a couple of letters by a certain former lawyer Eugen

Wilhelm—under the pseudonym “Numa Praetorius” he had for decades written

articles for the Yearbook for Sexual

Intermediates. Finally, there was a chance to find out something about the

fate of Eugen Wilhelm, which had looked

impossible before.

From his

letters to Hiller we learned that he had survived the Second World War and a period of incarceration in a

concentration camp (Schirmeck-Vorbruck). He had spent his last years with his

niece and his nephew “on our property in the Vosges mountains”—no proper names,

no exact place given. But, the dates of the letters made it possible to

determine a period within which Wilhelm must have died. So we asked a colleague

from Strasbourg, Régis Schlagdenhauffen, to look for a tomb at local

cemeteries and to search for persons who might be in charge of that tomb. He

came up with a large family tomb carrying so many names and dates that little

additional genealogical work was needed to identify the family. One of the

great nieces had the papers we were looking for, in another suitcase, that

originally was kept by Eugen Wilhelm’s sister, who was very fond of her gay

brother. It had been handed over to her daughter, and subsequently to her

granddaughter, with the words: “Some day someone will come who is interested in

that stuff.” “And now you are here,” said the great niece when our emissary

rang at her door. Among many other items, Eugen Wilhelm had kept a diary

between 1885 and 1951, the fifty-five volumes of which survive. The Magnus

Hirschfeld Society is working on an edition.[40]

Archives

There is

only one archive worldwide that has an original collection under the name of

Hirschfeld. The collection is known as “Hirschfeld scrapbook” and is at the

Kinsey Institute in Bloomington, Indiana.[41]

The name is a bit misleading, since the “scrapbook” is not a notebook or

something like that kept by Hirschfeld. Instead, it is a huge folio album

containing press clippings, correspondence, minutes of meetings of local SHC

groups, pictures, posters, brochures, and so on. Most of this originated from

the papers of the Hamburg SHC-member Carl Theodor Hoefft (1855-1927), and may

have been in the Institute after Hoefft had died. Additional loose items may

have been put into the album after the ransacking of the Institute.[42]

How this convolute came into the possession of Alfred Kinsey we could not find

out. Ernst Maass may have taken it after Hirschfeld’s death; or was it with Li

Shiu Tong, who for awhile lived in the U.S. during the Second World War (first at

Harvard University, then Washington, DC). A quite different way into Kinsey’s

collection is well possible.

It is

commonplace that there is always more material in archives than one had

expected. Expert archivists are invaluable in finding those treasures. I

remember the fun it was to exchange faxes (that was before the e-mail age, but

after the letter-writing ages) with Lesley Hall at the Wellcome Institute in

London, when I was preparing for a short stay there. As an answer to each and

every fax I sent I got something like, “If you are searching for X, you should

have a look at Y too, and in addition, we have Z”. Due to very limited

financial means and time I could only work with a small fraction of their

holdings, and I could only browse additional sources at the Department of

Western Manuscripts of the British Library.

Of similar

helpful expertise was Bianca Welzing at the Berlin State Archive. We knew, of

course, about the impotence remedy called “Titus Pearls” and its connection

with the original medication called “Testifortan”, manufactured in Hamburg by

Promonta. It was known, too, that the files of “Promonta” had been lost during

the war, and that the site of the “Titus” firm in East Berlin had been filled

with new buildings. What we did not know: The “Titus” files had survived due to

the fact that this pharmaceutical enterprise had been socialised after the war in

the German Democratic Republic and thus had become a state firm. That was why

their files ended up in the State Archive (normally, the files of private

enterprises are not within the scope of German State Archives). This voluminous

collection contains many details about the connection between the “Titus” firm,

“Promonta” in Hamburg, and the Institute for Sexual Science. It is even

possible to calculate the exact amount of money the Nazi authorities squeezed

out of the looted “Titus” licence.[43]

No restitution ever has been given for that.

From time

to time, searches in archives need a follow up. We knew for many years that the

German Literature Archive in Marbach has two items in their collection: the

Hirschfeld exile guestbook, and a correspondence with the writer Kurt

Tucholsky. When I recently experimented with their new online database to find

out how it works, I suddenly got three matches instead of the expected two.

There was an additional Hirschfeld autograph among the papers of the writer

Erich Kästner, together with a completely unknown private photograph of the cinders

of the Berlin book burning in 1933. Marita Keilson-Lauritz and I published this

little extra recently.[44]

Things Found by Chance

In the

early 1980s, an antiquarian book dealer offered two volumes to a friend that

had been in the former possession of Hirschfeld. Their provenance was clear,

since they were dedicated copies. And even more: The thief had entered his name

into the books: “Looted on May 6, 1933, by Fritz Krönker” is written in pencil

on the flyleaf. Unfortunately, we could not find this Fritz Krönker until now.

Other rare

book dealers offer books from the Institute’s library or from the estates of

former collaborators, friends, etc., every now and then. If the prices are

reasonable and our means allow the purchase, the Magnus Hirschfeld Society buys

such items.

While the

Nazi book burning was in preparation, one could read in the German press that,

of course, no works of scientific value would be burned, but only “dirt and

smut”.[45]

If this is true, in the case of the Institute’s library there should be more

undetected items somewhere in libraries. It was only very recently that we got

one of those from the Berlin Public Library. They are doing a complete revision

of their holdings and found that book on their shelves. It had been given to

the Public Library after the war together with many others which did not belong

to the Hirschfeld Institute. Unfortunately, the accession book has no

information where this book was between 1933 and 1945.

To make the

libraries’ research for the provenance of their books easier, we recently

published the typical library stamps and the shelf marks used by Hirschfeld, by

the Institute for Sexual Science, and by the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee.[46]

Typical Shelfmarks and

Library Stamps Used at Hirschfeld's Institute

Prominent Objects

Magnus

Hirschfeld’s exile guest book is, of course, one of the most important and most

interesting objects. It was even discovered twice, independently. Our discovery

story goes like this. Sometime after the death of a close common friend, his

partner packed his books. Among those, he found a copy of the catalogue

“Industriegebiet der Intelligenz”, which had accompanied an exhibit at the

Literaturhaus Berlin (25 Sept to 30 Oct 1988).[47]

We all had missed that exhibit. This catalogue, I was told over the phone,

contained a photograph of a Hirschfeld guest book. Not believing what I heard,

I nevertheless headed for the Heinrich-Heine-Bookstore at the Zoo station—the

only bookstore in West Berlin at that time that was open at night and could be

expected to have everything you needed in arts and literature. Of course, they

had it high up on their shelves. And there it was: Hirschfeld’s exile guest

book, on loan in Berlin from the German Literature Archive in Marbach, and we

had missed it. But, this mistake became an inspiration, and we brought the

guest book to Berlin again for our exhibit on the 75th anniversary

of the Institute’s foundation (Schwules Museum, Berlin, 1994).

There is a

different discovery story by Marita Keilson-Lauritz, and she has told it

herself some time ago, together with the fascinating story of the guest book.[48]

Her working copy of the guest book has been on display in various exhibits[49]

(and I do hope it will be here at the ALMS conference, too). It is such a huge

amount of work to decipher the about 200 autographical entries (many in foreign

languages and foreign alphabets), to identify their authors, and to reconstruct

their biographies and their connections with Hirschfeld. From those connections,

on the other hand, it is possible to reconstruct missing parts of Hirschfeld’s

biography.[50]

At the end of this immense amount of work we hope for a facsimile edition of

this unique document. The newly founded Federal “Magnus Hirschfeld” Foundation[51]

will have one of its central tasks here.

Marita Keilson-Lauritz' Working

Copy of the Hirschfeld Exile Guestbook on Display in Berlin, 2011/12 © Ralf Dose

I already

mentioned the second important ego-documents—Hirschfeld’s hand-written

“Testament. Heft II”, kept between 1929 and 1935. It is not exactly what one

would expect as a last will and testament, but contains additional notes that

Hirschfeld wanted to leave for those who would continue his work. From time to

time, there are intersections offering reviews of things that had happened

during the past months. This is especially true for the time of the trip around

the world and the years in exile. The book was not written continuously, and

sometimes Hirschfeld only took down names. Nevertheless, this booklet offers a deep

insight into Hirschfeld’s life and his feelings during the last seven years of

his life. I am preparing an annotated facsimile edition, amended with letters

and documents from the second suitcase donated by Rob Maass—e.g. Hirschfeld’s

passport (1928-33), and a scrapbook with notes from Ascona and the French

exile. Financial help from the Federal “Magnus Hirschfeld” Foundation will be

needed for this edition, too.

These two

documents from Hirschfeld’s life proved to be really a challenge when searching

for Hirschfeld’s cultural heritage. He travelled the world, and left traces

everywhere. Already before he left for his trip around the world (1930-32) Hirschfeld

had travelled frequently throughout Europe for lectures abroad, and we are sure

that we do not know all the local reports and reactions to these events. We get

to the limits of our language skills, too. In Europe alone we would have to

search from Moscow to Spain. For his sojourns and his exile in Switzerland,

Beat Frischknecht managed to find an abundance of details.[52]

Hirschfeld’s traces in India were followed by Veronika Fuechtner.[53]

Domestic Personnel

A bourgeois

household before 1933 relied on domestic personnel. Searching for those persons

is extremely difficult, and only in cases of long-time servants is there some

hope for results. If no names are known, sometime the old inhabitant’s

registers—kept by the local police—can help. If domestic personnel lived in the

household of the master, they would be on his index card. The same is true for

tenants without a household of their own, who had just rented one room in a

bigger flat.

Berlin’s

inhabitant’s register is a special case: the original central card index at the

Police President’s office at Alexanderplatz was destroyed by fire during the

war. After the Second World War, American occupation authorities ordered the

reconstruction of the card index

from duplicates kept at the local police precincts. As many local police

stations had been destroyed in wartime, there are necessarily huge gaps in the reconstructed

card index. And it is not in alphabetical order, but organized according to the

American soundex system. This reconstructed card index can be consulted at the

Berlin State Archive;[54]

a special application is needed, and there is a fee, even if the request leads

to nothing.

In the case

of Hirschfeld, there is no index card left. From the testament written in Nice

we knew two names: Hirschfeld’s personal servant before he left Germany was

Franz Wimmer, and then there was the old cook, Hinrike/Henrike/Henny

Friedrichs. We now know a bit more about the two, though not enough. A few

letters by Franz Wimmer to Hirschfeld we got by chance among the “additional

items”[55]

in an auction. Henny Friedrichs knew that Hirschfeld wanted to pay her a small

pension out of his estate, and she tried to claim that pension from the Nazi

authorities. There are a large number of other members of the domestic

personnel, of which we only know the names, and sometimes what kind of job they

had. Some of the names we were able to verify in the Berlin city directories.[56]

In the

course of our research, we got clues that a former domestic servant of the

Institute was still alive, but she lived a very remote life and avoided

contact. Given her increasing age, a common friend eventually arranged for an

“informal” meeting (a pre-Christmas Carol singing event). Thus, we had a chance

to express our interest in a more detailed conversation, which she granted soon

after. Adelheid Schulz—her maiden name was Adelheid Rennhack—served in the

household of the Institute between 1928 and 1933, and she turned out to be an

invaluable source of details from an everyday perspective.[57]

In addition, she had preserved a lot of letters, postcards, and photographs

from those years, which she called the happiest time of her life, because “I

was respected there as a human being”. She was present when the Institute was

ransacked in May, 1933, and she was able to save a few items from the

Institute. Adelheid Schulz passed away four months before her 100th birthday.

Her daughter and her granddaughter gave us some of those items from the

Institute, some of them are now on permanent loan in the Schwules Museum in

Berlin.

Adelheid Schulz Explaining

the Institute's Rooms, Using a Model of the Building. In Front: Her

Granddaughter Alexandra Ripa.

© Manfred Baumgardt, Schwules Museum Berlin 2002

Contemporaries

One person

who connected us directly with the 1920s and 1930s was the German emigrant

gynaecologist Hans Lehfeldt (1899-1993), of New York. Only half a year after we

had started our work, he contacted us and offered a lecture. We happily agreed,

though we had no idea at all whom he was nor what he really had to offer. As a

young physician, Dr. Lehfeldt had worked in one of the early Berlin birth

control clinics. He had been a member of the 1929 congress of the WLSR, became

a good friend of Norman Haire,[58]

and was even closer with Margaret Sanger[59]—thus,

he knew everyone personally whose names and importance we carefully had to

collect from the journals of the time. From then on, Hans Lehfeldt gave us a

lecture every year, and he was our honoured surprise guest when we opened our

research unit in summer, 1992.[60]

The

journalist Kristine von Soden, when researching for her dissertation project on

the birth control clinics of the Weimar Republic,[61]came

across Erika Kwasnik in Denmark. Her grandmother had done repair needlework for

Hirschfeld and for the Institute, and had taken her little Erika with her many

times. From Erika Kwasnik we got a report about her childhood with “uncle

Hirschfeld”[62],

and a rare photograph from 1917 showing Hirschfeld with a crowd of children of

the domestic personnel under a Christmas tree.

© Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin

Yet another

contemporary we met thanks to Kristine von Soden was Lilo Laabs (born Hehner).

As a young professional woman, Miss Hehner had worked as a social worker with

the prostitutes at Alexanderplatz. From time to time, she had accompanied

clients to the Institute.[63]

Talking with her, she told us about a friend of hers of the same age, who in

1933 had studied languages in Paris. She could go back and forth between Berlin

and Paris, and she served at least once as a courier for Hirschfeld. She never

opened the packages which were given to her in confidence. There was only one

item she could tell us about: a big lampshade decorated with images from

Pomerania. Hirschfeld had asked for that one because he longed for something

from his home. This lampshade, too, has vanished.

Actor

Michael Rittermann (1910-1989)—he escaped the Nazis in 1938 from Austria—was

one of the first contemporaries whom we could interview. He had a first

engagement in Berlin around 1928. Being beginners, we only knew a few names of

persons—mainly those of elderly physicians. And, thus, our questions did not

lead to much. Michael Rittermann eventually burst out into: “Had I ever known

that you would ask me all this one day, I would have taken some interest in

those guys. See, I was young then and only interested in holding hands with

Karl Giese and the other young ones frequenting his rooms. These old chaps in

the Institute weren’t of any interest.”

Quite a

different kind of contemporary we would have liked to have met—but he escaped.

In our first exhibit at the Berlin State Library in 1985[64]

we showed as a key item a big photograph of the ransacking of the Institute.

One sees two uniformed men in boots standing in a big heap of books, brochures,

and journals. One day, an elderly gentleman had his wife/partner take a

photograph of him in front of this picture. When they left, he told our guard:

“The left one [or did he say: the right one?] of those two guys, that’s me.” Before

our guard could recover from the shock, he had run away. Maybe, one day, we can

acquire that photograph of 1985?

Clients and Patients

In two

cases, we were able to obtain personal memories of Institute patients about

their treatment at the Institute.

Through a

radio broadcast, a former Hirschfeld patient who lived some place outside East

Berlin heard about us. Letters were exchanged, and, from time to time,

telephone calls (at that time between West Berlin and some places outside East

Berlin you still had to call the switchboard and pre-announce your call, the

line itself came hours later), and visits. Gerd Katter, a trans* person in

modern terms (f to m) had preserved some important proofs about his treatment

at the Institute, among those a so-called “transvestite pass”, which we got

after Katter passed away in 1995.[65]

A more

negative view on experiences at the Institute can be found in an interview that

Rosa von Praunheim conducted with Dr. Hanns G., who as a teenager had been

brought by his father to Hirschfeld for examination and treatment.[66]

From

Adelheid Schulz’ tales we knew that the painter Toni Ebel had been a patient at

the Institute, but we did not have any vital dates. We did find some data at

the archives of the East Berlin Academy of Arts. Later, there was more from a

file at the State Archive—Toni Ebel had claimed compensation as a Nazi victim.

But, there was nothing about the Institute or her former existence as a man.

Then, incidentally, we got information that the State Archive kept some 40.000

files about legal name changes in Berlin between 1912 and 1945. Only about a

thousand of those names have been indexed so far; the rest are waiting for

processing. I could not find the name of “Ebel” in the index book. The friendly

archivist suggested that I might process the rest of the boxes, which I had to

decline. Seeing my disappointed face, he himself then opened one of those boxes

and after ten minutes came back with the sought-for file: it lay on top of that

box. In this file, there was another curriculum vitae: this time written by

someone who was a male and had to argue why he wanted to be a woman. The

complete story is ready for publication, though still unpublished.

The story

of “Dorchen”, who had lived at the Institute for awhile and had worked in its

housekeeping, as well as those of many other patients of the Institute, has

been presented by Rainer Herrn in his thorough study on transvestitism and

transsexualism and the early sexual science.[67]

Autobiographies

Autobiographies

are always a good starting point, as long as one mistrusts all and every

so-called “dates” and “facts”—better check yourself. In Hirschfeld’s case we

had his notes— “Von Einst bis jetzt”[68]—

which give a lot of details about the homosexual movement, but little about his

private life. Then there is an “autobiographical sketch” in a sexological

handbook from the United States.[69]

About his family background, there was a bit in the little booklet published on

the occasion of the 100th birthday of his father Hermann Hirschfeld, issued by

Magnus together with his sister Franziska Mann.[70]

“Women East and West”[71],

too, gives some biographic details; and in the course of our ongoing research

we have found additional brief pieces.

Many of the

prominent visitors of the Institute wrote autobiographies, or had a biography

written about them. From those, we got at least momentary insights, and

sometimes even clues for estates where a search might be useful. One well-known

example may be mentioned: Christopher Isherwood. His autobiographical novel Christopher and His Kind[72]

reveals that he had lived for awhile at the Institute; and there are names mentioned

(like Erwin Hansen) that cannot be found elsewhere.[73]

Any attempt to find out more details about his stay seemed useless. Allegedly,

Isherwood himself has destroyed the diaries of those years.[74]

Huntington Library staff kindly sent us a collection of Isherwood’s photographs

from Berlin. Unfortunately, we could not identify anyone in these pictures, and

there was no picture of the Institute’s building. Much later we found out that

such photographs exist nevertheless: at least one portrait of Karl Giese must

be in Isherwood’s papers.

This makes

very clear that in spite of all of the kind help by local archivists, personal

examination is crucial in the case of such papers. Only the researcher

himself/herself can produce all the necessary associations in order to find

more stuff. This necessity, then, hints to a general and structural problem:

non-university GLBT history research simply is not funded in a way that would

make a three-week-trip to Los Angeles possible. Let’s change that.

Bibliographies and Reception

When we

started, there was no bibliography of Hirschfeld’s writing. James D. Steakley

provided a much needed first compilation.[75]

I know that this little book was at hand at the help desk of the Berlin State Library.

I remember very well the disappointed look in the faces of the librarians on

duty, when they learned that we not only knew this booklet but had helped to

publish it, and were now searching for something that was not in their book.

A complete

bibliography (including reviews) is still a desideratum. Jim Steakley’s

database for a second edition of his bibliography is growing and growing. A

complete list of all the expertise given in court by Hirschfeld and his

colleagues from the Institute will never be possible. Though the Hirschfeld

Society was able to do some preliminary work on the reception of Hirschfeld’s

writings and theories,[76]

there is a lot of work still to be done.

Items Which Are Missing

and Which We Are Looking For

From his world trip, Hirschfeld sometimes sent home

items he had collected locally. According to Adelheid Schulz’ tales (confirmed

by others), there was a big Indonesian phallic stone statue, which was

displayed at the Institute. She still chuckled about the faces of the customs

people when unpacking this item. Simply because of its weight the Nazis must

have had problems moving this statue. This one is still missing, as well as

many other objects from the Institute. Among those missing objects is the door

of a men’s house from New Guinea, which had been in the Institute’s collection

earlier. It was last seen seen in Nice in 1936, at that time possessed by a

certain “VB.” Where is it now, and where are all the other things that “VB” had

in his hands in 1936?

Some

background information may be needed. All patients and visitors of the

Institute were asked to fill in the so-called Psycho-biological Questionnaire.

How many of these questionnaires existed is not clear. Ludwig Levy-Lenz gives a

figure of some 40,000. Hirschfeld mentioned in 1935 that it had been possible

to save those questionnaires from the Nazis, and that Karl Giese could bring

more than 1,000 of them to France. It is unclear where they went. Presumably,

many were destroyed, as Henri Nouveau/Henrik Neugeboren (1901-1959) noted in

his diary, 14 February 1936:

Hirschfeld’s picture archive: Exactly eleven years ago I had visited

Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin, who has died recently in Nice, but did not have a

chance to see his ill-reputed collection.

And now, on my first night

in N. […], VB showed me Hirschfeld’s complete picture archive which had not

been burnt in Berlin—as it was said—but was bought back by H.’s lawyer for the

immense sum of 35-40,000 M under the condition that it was brought out of the

country.

I have never tried to

understand how VB came into the possession of this part of the estate […] This

whole heap was given to me as scientific worthless so that I should make photo

montages or whatever I wanted to do. I made for VB and for myself some more or

less well done montages, […] kept about 50 for myself and gave back the rest.

VB gave me also a pornographic japan. woodprint, ‘the bark’, and possessed a

lot of most beautiful pornogr. kakemonos. – Before I moved downstairs, I slept

upstairs, […] under the magnificent entrance door of a Melanesian men’s house[77],

which VB late had to give back… Days and nights the many 100s of filled-in

questionnaires were browsed; I, too, read a lot of them after strict confidence

had been asked from me. […] Much was burnt; I myself put several filled waste

paper baskets, given to me by VB for a last search for “valuables” that might

have gotten into them in error, into the central heating of the house. […] It

was said that all this happened with approval of the French state attorney.[78]

Marita

Keilson-Lauritz and I recently detected that “VB” was the the painter and

musician Victor Bauer.[79]

Maybe, the process how we traced “VB” within a two days correspondence is of

some interest. It started with a copy of my paper for the conference on “Looted

Books and Libraries of Former Jewish Possession,” which I had sent to Marita.

The quotation above is included in this paper. In Marita’s reply, she alerted

me about a finding from the Internet. In 1994, a certain Eberhard Berger had

written a dissertation on Henri Nouveau and his “sexual diary”—when I read it

later on, I found that it did not contain any helpful hints. In a second message,

Marita suggested checking “Viktor Bausch”, a paper mill owner and antifascist,

because there were some connections between him and the politicians and

Nazi-resisters Theodor Haubach and Carlo Mierendorff, who on their side had

contacts with the SHC. Finally she added to the list a “Viktor Brauner”, a

Rumanian surrealist, from the index of Peter Gorsen’s book on “Sexualästhetik”.

Brauner could be excluded quickly—he had moved to Bucharest in 1935 and

therefore could not have lived in Nice in 1936. I could not find any hints concerning

Viktor Bausch in Nice. After I did not find anything on Google searching for

“Viktor Bausch” and “Nizza”, I omitted “Bausch” and searched again for “Viktor”

and “Nizza”. This time, the websites of two art galleries showed up,

representing a “Victor Bauer” who was said to have been connected with Wilhelm

Reich and Hirschfeld. Additional literature searches quickly confirmed that

Victor Bauer was “VB”. Alas, this did not solve the mystery of Hirschfeld’s

estate. The artist’s widow, who was a friend of the Hamburg sexual scientist

Hans Giese in the 1950s and 1960s, and had given part of the estate of her late

husband, had been his second wife; they were married after WW II. She did not

know (or did not tell) anything about what happened in 1936. We have not been

able to determine the fate of Victor Bauer’s first wife—a certain Irmgard

Strauss.

There is

more to do: Where are Hirschfeld’s diaries? Where are those items he put into

the storage room of Bedel & Co. in Paris?

Loose Ends

There are

many more traces that we could not follow so far due to lack of time and money.

Here are a few examples. Someone should check the papers of George Sylvester

Viereck. There was not only a friendship with Hirschfeld, but an acquaintance

with his sister Franziska, too. The evil role Viereck played as a Nazi

representative in the United States makes this research even more necessary.

Even the

papers collected by Erwin J. Haeberle for his Archive for Sexology[80]

have not been read completely. With respect to the Institute for Sexual Science

there are papers of Harry Benjamin, of Bernhard Schapiro, and of Ludwig

Levy-Lenz.[81]

Finally,

there was a newsreel showing Hirschfeld, which was made in New York early in

December 1930 by Fox Movietone. This newsreel was screened shortly before Christmas

1930 in New York City at the “Embassy” theatre, but not nationwide. The

newsreel seems to be lost, since very few copies may have existed. But, who

knows?[82]

Conclusion

Reviewing

some thirty years of research on the estate of Magnus Hirschfeld and of the

Institute for Sexual Science, there is a very simple result: one thing leads to

another. Any found bit of information includes some kind of extra detail which at

the moment may not mean anything, because a name or a place does not trigger

any association, or because there are no material resources, or because

archival sources exist but have not been catalogued (or digitized), or because

the Internet does not exist ….

Therefore,

the overall rule is: write down and keep safe any bit of information. The next

generation of researchers could just need this single detail to be successful.

Mary (Maria) Saran, Max Hodann’s first wife, choose as the title for her

autobiography Never Give Up.[83]

That is a good motto for our work, too.

References

Baumgardt,

Manfred (1984a): Hirschfelds Testament. In: Mitteilungen

der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (4), pp. 7–12.

Baumgardt,

Manfred (1984b): Das Institut für Sexualwissenschaft und die

Homosexuellenbewegung in der Weimarer Republik. In: Berlinische Galerie (ed.): Eldorado. Homosexuelle Frauen und

Männer in Berlin 1850-1950. Geschichte, Alltag und Kultur. 1. Auflage. Berlin:

Frölich und Kaufmann, pp. 31-41

Baumgardt,

Manfred (2000): Die Abwicklung des Instituts für Sexualwissenschaft (I.f.S.):

Die Prozesse und ihre Folgen (1950-1965). In: Schwule Geschichte (4), pp. 18–40.

Baumgardt,

Manfred (2003): Kaffeerunde mit Adelheid Schulz. In: Schwule Geschichte (7), pp. 4–16.

Baumgardt, Manfred; Dose, Ralf; Herzer, Manfred; Klein,

Hans-Günter (1985): Magnus Hirschfeld – Leben und Werk. Ausstellungskatalog. 1. Aufl. Westberlin: rosa

Winkel.

Berner,

Dieter (1989a): Zur Fundgeschichte von Tao Li's Namenszug. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (13), pp. 5–7.

Berner,

Dieter (1989b): Eine Lektion in Chinesisch. In: Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (14), pp. 5–8.

Bowers,

Q. David/Doty, Richard G. (2002): A California Gold Rush History featuring the

treasure from the SS Central America: a source book for the gold rush historian

and numismatist. Newport Beach, CA.

Dose, Ralf (1991a): Aufklärungen über “Die Aufklärungˮ – Ein

Werkstattbericht. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (15), pp. 31–43.

Dose,

Ralf (1991b): Register für “Die Aufklärung” bzw. “Aufklärung und Fortschritt”.

In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (16), pp. 57–76.

Dose, Ralf (1993): Thesen zur Weltliga für Sexualreform – Notizen

aus der Werkstatt. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (19), pp. 23–39.

Dose,

Ralf (1994): Erinnerungen an Hans Lehfeldt (1899-1993). In: Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung 7 (1), pp.

70–78.

Dose, Ralf (1996): No Sex Please, We're British, oder: Max

Hodann in England 1935 – ein deutscher Emigrant auf der Suche nach einer

Existenz. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (22-23), pp. 99–125.

Dose,

Ralf (1997): No sex, please, we're British o: Max Hodann en Inglaterra en 1935,

un emigrante alemán a la búsqueda de una existencia. In: Anuario de sexología 3, pp. 135–159.

Dose,

Ralf (1999): The World League for Sexual Reform: some possible approaches. In:

Franz X. Hall Lesley Eder und Gert Hekma (eds.): Sexual Cultures in Europe.

National Histories. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 242–260.

Dose,

Ralf (2003a): In memoriam Li Shiu Tong (1907-1993). Zu seinem 10. Todestag am

5.10.2003. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (35/36), pp. 9–23.

Dose,

Ralf (2003b): The World League for Sexual Reform. Some Possible Approaches. In:

Journal of the History of Sexuality 12

(1), pp. 1–15.

Dose,

Ralf (2004): Die Familie Hirschfeld aus Kolberg. In: Elke-Vera Kotowski und

Julius H. Schoeps (eds.): Magnus Hirschfeld. Ein Leben im Spannungsfeld von

Wissenschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft. Berlin: be.bra wissenschaft verlag

(Sifria. Wissenschaftliche Bibliothek, 8), pp. 33–64.

Dose,

Ralf (2005): Magnus Hirschfeld. Deutscher – Jude – Weltbürger. Teetz: Hentrich

& Hentrich (Jüdische Miniaturen, 15).

Dose,

Ralf (2011): Es gibt noch einen Koffer in New York. In: Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (46-47), pp. 12–20.

Dose,

Ralf; Herrn, Rainer (2005): Um das Erbe Magnus Hirschfelds. In: AKMB news 11 (2), pp. 19–23.

Dose,

Ralf; Herrn, Rainer (2006): Verloren 1933: Bibliothek und Archiv des Instituts

für Sexualwissenschaft in Berlin. In: Regine Dehnel (ed.): Jüdischer Buchbesitz

als Raubgut. Zweites Hannoversches Symposium. Frankfurt a.M.: Vittorio

Klostermann (Zeitschrift für

Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie. Sonderheft, 88), pp. 37–51.

Dose, Ralf; Keilson-Lauritz, Marita (2010): “Vielen Dank,

Erich Kästner!ˮ Die Berliner

Bücherverbrennung – am Morgen nach der Tat. In: Julius H. Schoeps und Werner

Treß (eds.): Verfemt und Verboten. Vorgeschichte und Folgen der

Bücherverbrennungen 1933. Hildesheim, Zürich, New York: Georg Olms

(Wissenschaftliche Begleitbände im Rahmen der Bilbiothek Verbrannter Bücher,

2), pp. 169–176.

Dose,

Ralf; Klein, Hans-Günter (eds.) (1992): Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft. Band I: Heft 1 (1983) - Heft 9 (1986) Band II:

Heft 10 (1987) - Heft 15 (1991). Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V. Second,

revised, and amended ed. 2 vols. Hamburg: von Bockel.

Dubout,

Kevin (2011): Eugen Wilhelms Tagebücher. Editorische Probleme, Transkriptions-

und Kommentarprobe. In: Officina editorica, Bd. 10, pp. 215–304.

Engelmann, Peter (1999/2000): Zervixkappen als “Bonbons

aus Frankreichˮ und andere Einblicke und Ereignisse aus der Arbeitsfreundschaft

zweier Pioniere der Geburtenregelung. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (31-32), pp. 29–39.

Frischknecht, Beat (2009): “Der Racismus – ein Phantom als

Weltgefahrˮ. Der Fund eines

verschollenen Typoskripts als Auslöser umfangreicher Recherchen. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (43-44), pp. 21–34.

Fuechtner,

Veronika (2013): Indians, Jews and Sex: Magnus Hirschfeld and Indian Sexology.

In: Veronika Fuechtner and Mary Rhiel (eds.): Imagining Germany Imagining Asia:

Essays in Asian-German Studies. Rochester: Camden House, forthcoming.

Herrn,

Rainer (2004): Vom Traum zum Trauma. Das Institut für Sexualwissenschaft. In:

Elke-Vera Kotowski und Julius H. Schoeps (eds.): Magnus Hirschfeld. Ein Leben

im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft. Berlin: be.bra

wissenschaft (Sifria. Wissenschaftliche Bibliothek, 8), pp. 173–199.

Herrn,

Rainer (2005): Schnittmuster des Geschlechts. Transvestitismus und

Transsexualität in der frühen Sexualwissenschaft. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag

(Beiträge zur Sexualforschung, 85).

Herrn,

Rainer (2010): Magnus Hirschfelds Institut für Sexualwissenschaft und die

Bücherverbrennung. In: Julius H. Schoeps und Werner Treß (Hgs.): Verfemt und

Verboten. Vorgeschichte und Folgen der Bücherverbrennungen 1933. Hildesheim,

Zürich, New York: Georg Olms (Wissenschaftliche Begleitbände im Rahmen der Bibliothek

Verbrannter Bücher, 2), pp. 113–168.

Herzer,

Manfred (1997): In memoriam Günter Maeder (*13.1.1905 in Berlin + 3.1.1993 in

Berlin) mit einer Beilage: Vier Briefe von Christopher Isherwood an Günter

Maeder. In: Capri (23), pp. 16–18.

Herzer,

Manfred (2005): In memoriam Erhart Löhnberg. In: Capri (37), pp. 19–24.

Hirschfeld,

Magnus (1919): Franziska Manns Lebenseintritt: Eine wahre Geschichte. In:

Franziska Mann: Der Dichterin – Dem Menschen! Zum 9. Juni 1919. Mit Beiträgen

von Hedwig Dohm, Ellen Kay, Arthur Silbergleit und Magnus Hirschfeld. Jena:

Landhausverlag, pp. 13–16.

Hirschfeld, Magnus (1933): Die Weltreise eines

Sexualforschers. Brugg:

Bözberg.

Hirschfeld,

Magnus (1935): Women East and West. Impressions of a Sex Expert. English

Version by O. P. Green. London: William Heinemann.

Hirschfeld,

Magnus (1938): Le Tour du monde d’un sexologue. Traduction: L. Gara.

Paris: Gallimard

Hirschfeld,

Magnus (1986): Von einst bis jetzt. Geschichte einer homosexuellen Bewegung

1897-1922. Westberlin: rosa Winkel (Schriftenreihe der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft, 1).

Hirschfeld, Magnus; Mann, Franziska geb. Hirschfeld

(1925): Zum 100. Geburtstag von S.-R. Dr. Hermann Hirschfeld. Zwei Aufsätze für

die Kolberger Zeitung für Pommern. Kolberg: C.F. Post.

Isherwood,

Christopher (1985): Christopher and His Kind 1929-1939. New ed. London:

Methuen.

Katz,

Jonathan Ned (ed.) (1975): A Homosexual Emancipation Miscellany, c. 1835-1952.

New York: Arno Press.

Keilson-Lauritz,

Marita (2004): Magnus Hirschfeld und seine Gäste. Das Exil-Gästebuch 1933-1935.

In: Elke-Vera Kotowski und Julius H. Schoeps (eds.): Magnus Hirschfeld. Ein Leben

im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft. Berlin: be.bra

wissenschaft (Sifria. Wissenschaftliche Bibliothek, 8), pp. 71–92.

Keilson-Lauritz, Marita (2006): Hirschfelds Gäste. Eine

Ausstellung zu einem Exil-Gästebuch. In: Hinter

der Weltstadt. Mitteilungen des Kulturhistorischen Vereins Friedrichshagen

(14), pp. 13-16.

Keilson-Lauritz, Marita (2008): “Ein Rest wird übrig

bleiben…ˮ Hirschfelds Gästebuch als biographische Quelle. In: Mitteilungen

der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (39-40), pp. 36–49.

Keilson-Lauritz,

Marita (2011): Erinnerungspunkte. Überlegungen zur Arbeit am Exil-Gästebuch

Magnus Hirschfelds. In: Subjekt des Erinnerns? Zwischenwelt 12.

Theodor-Kramer-Gesellschaft (ed.) (= Jahrbuch für antifaschistische Literatur und Exilliteratur,

12), pp. 59-70

Keilson-Lauritz, Marita; Dose, Ralf (2009): “Für die

Echtheit der Handschrift verbürge ich mich.ˮ Ein Tagebuch-Fragment Magnus

Hirschfelds im Nachlass von Erich Kästner. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (43-44), pp. 9–20.

Keilson-Lauritz, Marita; Pfäfflin, Friedemann (1999): “Unzüchtig

im Sinne des § 184 des Strafgesetzbuchs”. Drei Urteilstexte und ein Einstellungsbeschluß. In: Forum Homosexualität und Literatur (34), pp. 33–98.

Keilson-Lauritz,

Marita; Pfäfflin, Friedemann (2000): Die Sitzungsberichte des

wissenschaftlich-humanitären Komitees München 1902-1908. In: Capri (28), pp. 2–33.

Keilson-Lauritz,

Marita; Pfäfflin, Friedemann (eds.) (2002): 100 Jahre Schwulenbewegung an der

Isar I: Die Sitzungsberichte des Wissenschaftlich-humanitären Comitees München

1902-1908. München: Forum Homosexualität und Geschichte e.V. (Splitter. Materialien

zur Geschichte der Homosexuellen in München und Bayern, 10).

Kinder,

Gary (1998): Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea. New York, NY: The Atlantic

Monthly Press.

Klein,

Hans-Günter (1986): Beiträge zu einer Bibliographie der unselbständigen Veröffentlichungen

Kurt Hillers. 1. “Mitteilungen des Wissenschaftlich-humanitären Komitees” und “Der

Kreis”. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (9), pp. 31–34.

Klein,

Hans-Günter (1987a): Beiträge zu einer Bibliographie der unselbständigen Veröffentlichungen

Kurt Hillers. 2. “Die Schaubühne” bzw. “Die Weltbühne”. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (10), pp. 39–48.

Klein,

Hans-Günter (1987b): Streiter ohne Maß mit Ziel. Zum 15. Todestag von Kurt

Hiller. In: rosa flieder (54

(August-September)), pp. 6–7.

Klein,

Hans-Günter (1988a): Beiträge zu einer Bibliographie der unselbständigen

Veröffentlichungen Kurt Hillers. 3. “Lynx”. In: Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (12), pp. 44–49.

Klein, Hans-Günter (1988b): Kurt Hiller – die zentralen

Bereich seines schriftstellerischen und organisatorischen Engagements. In: Mitteilungen der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (11), pp. 7–16.

Klein, Hans-Günter (1990a): “Ich bin zum Denken verdammt;

das trägt nichts ein!” Kurt

Hillers Misere im Exil. In: Rolf von Bockel (ed.): Kurt Hiller. Ein Leben in

Hamburg nach Jahren des Exils. Unter Mitarbeit von Wolfgang Beutin, Martin

Klaußner, Hans-Günter Klein und Harald Lützenkirchen. Hamburg: Bormann-von

Bockel edition hamburg, pp. 15–19.

Klein,

Hans-Günter (1990b): Kurt Hillers strafrechtspolitisches Engagement und die

Neugründung des Wissenschaftlich-humanitären Komitees 1962. In: Rolf von Bockel

(ed.): Kurt Hiller. Ein Leben in Hamburg nach Jahren des Exils. Unter Mitarbeit

von Wolfgang Beutin, Martin Klaußner, Hans-Günter Klein und Harald

Lützenkirchen. Hamburg: Bormann-von Bockel edition hamburg, pp. 28–33.

Klein,

Hans-Günter (1991): Beiträge zu einer Bibliographie der unselbständigen

Veröffentlichungen Kurt Hillers. 4. Literarische Aufsätze 1910 - 1. August

1914. In: Mitteilungen der

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (15), pp. 44–51.

Klein, Hans-Günter (2000): Kurt Hiller und die “Schmach” des

20. Jahrhunderts. Anmerkungen

zu zwei Briefen an Erich Ritter 1948. In: Mitteilungen

der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (31-32), pp. 40–46.

Kokula,

Ilse (1984): Persönliche Erinnerungen. In: Mitteilungen

der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (3), pp. 35–37.

Kokula,

Ilse (1986): Dora Russell. In: Mitteilungen

der Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (9), pp. 12–13.

Krey, Friedhelm